The Forgotten Voices of British Abolitionism

Part Two: The Sons of Africa

As I mentioned in part one, the historical memory of Olaudah Equiano has been such that he has come to exemplify the lack of enslavement on British soil. In reality, however, Equiano was a contemporary of not only other enslaved and free Blacks in 18th-century London, but also partnered with Black men committed to the abolition of slavery. Their organization is the oft-forgotten: The Sons of Africa.

The Sons of Africa: Members

Established in the late 1700s, the Sons of Africa was a London-based abolitionist organization comprised of formerly enslaved men and descendants of enslaved people. The group is considered to be Britain’s first Black political organization, and played a crucial role in the abolitionist movement that often gets overlooked. The members of The Sons of Africa were freed enslaved men who had once toiled in America and the Caribbean, but also on British soil. Each had secured their freedom, which they used to become educated and aid in the ending of slavery.

Portrait of Olaudah Equiano, accessed via: Black History Month

Twelve men made up the organization: Olaudah Equiano, Ottobah Cugano, Boughwa Gegansmel, Jasper Goree, Cojoh Ammere, George Robert Mandeville, Thomas Oxford,

George Wallace, William Stevens, Joseph Almze, James Bailey, and John Christopher.

Col. Richard Cosway; Maria Louisa Catherine Cecilia Cosway (née Hadfield); probably Ottobah Cugoano, by Richard Cosway. Accessed via: National Portrait Gallery

etching, 1784laborative Abolitionist Efforts

Abolitionism is best understood as an ensemble movement, dependent on the interconnected efforts of a myriad of actors. British abolition was marked by the enslaved themselves, the Sons of Africa, but also the efforts of Quakers, other religious groups, parliamentarians, philanthropists, and scholars like Granville Sharp and Thomas Clarkson- the founders of The Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, a white abolitionist organization. Together with the Sons of Africa, over decades, these marginal groups gained traction and made abolition a central conversation in British social and political discourse at the end of the 18th century. The Sons of Africa contributed significantly to this movement by lobbying Parliament and the Crown, making speeches in the public square, and rallying support from British aristocrats and ordinary people. Their words, in writing and speech, reached the nation, presenting Britain with living proof of Black humanity and capacity, directly contradicting pro-slavery ideologies of Black inferiority and suitability for enslavement.

The autobiographies of Equiano and Cugano became bestsellers, stoking the interest of the public in the hidden horrors of Caribbean and American slavery. By foregrounding their experiences of vicious brutality at the hands of enslavers, highlighting the violence of overseers and the family destruction central to slavery, their narratives pushed forward British abolitionism, which originally focused on ending the slave trade, by forcing them to also prioritize the emancipation of the enslaved. This is a seismic contribution that their first-hand narratives made to the movement, humanizing the enslaved who toiled in fields an ocean away, forcing the nation to behold the human cost of slavery. Further, they added the (sadly) necessary first-hand experience to authenticate the moral authority of abolitionism, forming a powerful voice that could not be long ignored.

Not only did The Sons of Africa shape the British abolitionist movement, but they also influenced public opinion and the push for antislavery legislation, namely in the Zong Massacre case and the passing of the 1788 Slave Act.

The Sons of Africa, the Zong Massacre, and the 1788 Slave Act

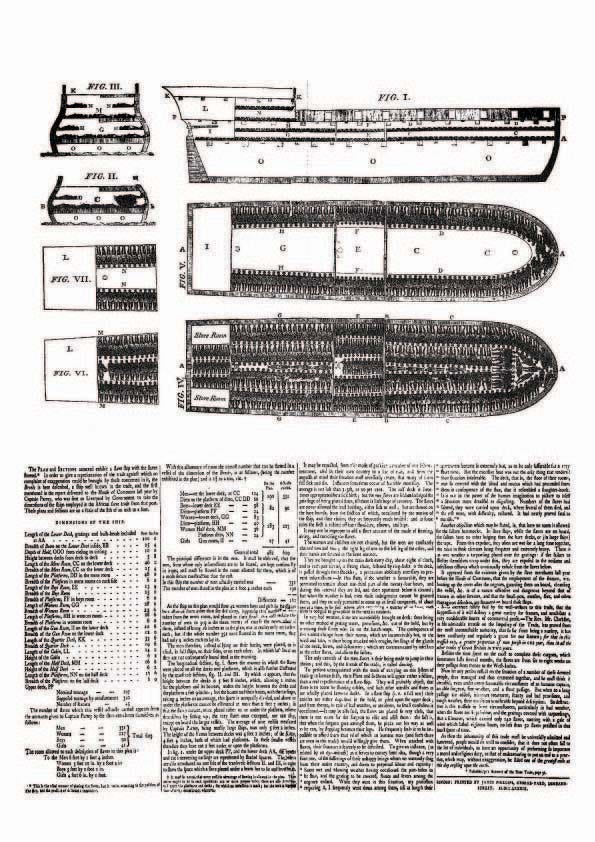

The horrors of the Transatlantic Slave Trade and the experiences of Africans forced aboard ships transporting them through the Middle Passage into the “New World” served as the centerpiece of abolitionist denunciation of slavery. The imagery of slave ships we know today is a result of abolitionist efforts to depict the horrors of the trade, printing diagrams on pamphlets to distribute across the nation. Ottobah Cugano’s narrative of his enslavement, entitled Thoughts and Sentiments on the Evil and Wicked Traffic of the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species (1787), recalls that the experience aboard a slave ship was too traumatic to describe. In his narrative, Equiano describes slave ships as a “scene of horror almost inconceivable,” and memories of “a multitude of black people of every description chained together,” the captives packed in quarters “so crowded that each had scarcely room to turn himself.” Their narratives worked in conjunction with the “Description of a Slave Ship” diagram commissioned by Thomas Clarkson, which he intended to evoke an “instantaneous impression of horror upon all who saw it,” inspiring them to join the abolitionist cause.

Print of “Description of a Slave Ship, originally printed as posters and pamphlets in 1778. Accessed via: Understanding Slavery

However, the horrors of the trade were brought into British consciousness in 1783, five years before the widespread distribution of Clarkson’s image, through the harrowing case of the Zong Massacre. In 1781, a Liverpool-registered slave ship named the Zong set sail with 442 enslaved people aboard; twice the human cargo the ship was designed to carry without innumerable deaths. However, three months into the voyage, as a result of crew errors in navigation and a rampant outbreak of disease among the captives, the crew ascertained that they would quickly run out of freshwater and supplies. In a ruthless effort to preserve their profits, the crew cast 133 of the most unwell enslaved people overboard over the course of three days. This “clinical massacre of innocents” proved to be worse still, a feat of callous incompetence, when the ship arrived in Jamaica with 420 gallons of freshwater to spare.

The incident became widely known two years later when one of the Zong owners attempted to file an insurance claim against the “loss” of cargo, demanding repayment of thirty pounds for each enslaved person he had elected to murder. Equiano and the Sons of Africa were some of the first to notice the claim reported anonymously in newspapers in London. The case landed in court as the insurance company refused to pay, and to the legal system, this was simply an insurance dispute. However, the Sons of Africa actively worked to keep the story in the public eye, reframing it in its true light: a demonstration of the inhumane treatment of the enslaved aboard slave ships, and a harrowing depiction of the truth of human property. Their efforts shaped the beginnings of formal abolitionism in the UK, but ultimately, the court ruled that the insurance company was liable for damages because it deemed enslaved property the same as any other property.

Joseph Mallord William Turner, Slave Ship (Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying, Typhoon Coming On). Accessed via: Smart History

In 1788, abolitionist William Dolben sought to stem the tides of the Transatlantic Slave Trade by proposing a law that limited the number of enslaved people legally allowed to be transported aboard a slave ship. Likely inspired by the horrors of the Zong Massacre, Dolben argued for the law to limit the number of enslaved people allowed aboard a ship bound for the New World. The law stated that a ship had to:

to have on board, at any one time, or to convey, carry, bring, or transport slaves from the coast of Africa, to any parts beyond sea, in any such ship or vessel, in any greater number than in the proportion of five such slaves for every three tons of the burthen of such ship or vessel, so far as the said ship or vessel shall not exceed two hundred and one tons; and moreover, of one such slave for every additional ton of such ship or vessel, over and above the said burthen of two hundred and one tons, or male slaves who shall exceed four feet four inches in height, in any greater number than in the proportion of one such male slave to every one ton of the burthen of such ship or vessel, so far as the said ship or vessel shall not exceed two hundred and one tons, and (moreover) of three such male slaves (who shall exceed the said height of four feet four inches) for every additional five tons of such ship or vessel, over and above the said burthen of two hundred and one tons . . . and if any such master, or other person taking or having the charge or command of any such ship or vessel, shall act contrary hereto, such master, or other person as aforesaid, shall forfeit and pay the sum of thirty pounds of lawful money of Great Britain, for each and every such slave exceeding in number the proportions herein-before limited . . .

II. Provided always, That if there shall be, in any such ship or vessel, any more than two fifth parts of the slaves who shall be children, and who shall not exceed four feet four inches in height, then every five such children (over and above the aforesaid proportion of two fifths) shall be deemed and taken to be equal to four of the said slaves within the true intent and meaning of this act. . . .

In short, Dolben, hoping to limit the horrors of the Middle Passage, sought to limit the number of enslaved adults aboard a ship. He also outlined that no more than ⅖ of a ship’s cargo should be children. The Sons of Africa lobbied parliament and offered their support to Dolben in the hopes that it would transform the Transatlantic Slave Trade and make it less profitable. The law was passed, but slavers simply pivoted their trade to include more children who met the height restrictions, dragging an increased number of African children into the trade away from families. It also sparked discourse on the benefits of slave breeding over and above buying them, making this legislation a key catalyst for the increased sale of children and girls after 1788.

The Long Fight

The British abolitionist movement faced a long fight, in which the establishment and commercial law continued to win, until they successfully lobbied Parliament to pass the abolition of the trade in 1807 and the ending of slavery in the British Caribbean in the 1830s. The loss of the Zong case and the inadvertently dire consequences of the 1788 slave act evidence the commitment to the trade and institution of slavery held by those in power in the late 18th century. Nonetheless, throughout the years, the Sons of Africa and countless forgotten Black abolitionists fought to bring an end to the enslavement of their kin across the New World.