The Forgotten Voices of British Abolitionism

Part One: Runaway Slaves as Crucial Abolitionists

Abolitionism became a central to Britain’s national mythology after it abolished the slave trade and slavery in the first half of the 19th century. If slavery is mentioned in schools, it is often only to celebrate Parliament’s resolution to end slavery, and William Wilberforce as the abolitionist icon who dedicated his life and political career to that end. Lesser discussed are the Black people whose objections to the institution of slavery and the trade contributed to the decades-long abolitionist movement in Britain. There are only a handful of Black abolitionists who had the connections and standing to have their voices heard; thus, the small number is reflective of the lack of access Black Brits had to the ears of the establishment. Additionally, in the famous Sommerset Trial of 1772, slavery was finally made illegal on British soil, slowing the influx of Africans brought into the nation. Nonetheless, Black abolitionists allied with white sympathizers to the cause, aiding in the formation of legal, philosophical, and religious objections to slavery. The most famous is Olaudah Equiano, a man formerly enslaved in Barbados and Virginia, until he was sold to a ship captain in London, where he worked as an enslaved deckhand, valet, and barber. Equiano traded on the side, saving his earnings well enough to purchase his freedom within three years. In 1786, he joined the abolitionist movement in London, lending his voice to the cause in the form of his (now famous) slave narrative: ‘The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano or Gustavus Vassa, the African.’

However, Equiano is far from anomalous in the British abolitionist movement, but, rather, is only exceptional in the fact that we acknowledge and remember him. Allow me to introduce you to a few Black voices that fueled the abolitionist movement in Britain.

The Convoluted Case of Mary and John Hylas- Hylas v. Newton

Oftentimes, abolitionism is understood simply as a systematized movement, often obfuscating the attacks against the institution levelled by enslaved people themselves through revolt or petitioning for freedom. Contrastingly, I argue that what organized abolitionism had in rhetoric served as a mere reflection of philosophies first enlivened by enslaved people themselves through their direct resistance to the institution of slavery, no matter the level of their success.

Countless enslaved people in Britain dared to defy their status as property, staking their claim to freedom by running away.

One such case is that of Mary Hylas, an enslaved woman married to a free Black man, John Hylas. Mary Hylas was born in Barbados in the early 18th century on the Newton plantation on the coast of the island, and John Hylas was an enslaved manservant to her mistress’s sister. By 1754, both were forced to accompany their mistresses on an extended trip to England as their enslaved property. Mary and John married four years later, and John claimed his freedom after the death of his mistress in 1763, choosing to continue living as a free man in London. Contrastingly, his wife, Mary, was forced to leave her husband behind and return to the Newton plantation in Barbados. John Hylas filed to sue the Newtons for taking his wife away without his consent and sought monetary damages. The case went to trial in 1768. Unexpectedly, Hylas won, and the Judge demanded that the Netwons pay damages, return Mary to her husband, or receive further penalties. Mary Hylas had no entitlement to freedom according to British law, but she won her freedom based on the court’s concession that her husband’s rights held legal sway over those of her owner. John Hylas won this case, but curiously, Mary never returned to England and continued to live in Barbados as an enslaved woman on the Newton plantation. This case demonstrates the failing omnipotence of white slaveowners in 18th-century England in the face of British law, but simultaneously reveals the power enslavers derived from distance. It also illuminated the limitations of loopholes available for enslaved people, especially women, for accessing freedom. The lack of legislation surrounding slavery on British soil yielded an uneven and unpredictable hand of the law, allowing it to work to the benefit of the enslaved (Mary was technically free) on occasion but to their detriment on others (Mary was in Barbados, where slavery was untouchable), even in the same court case.

Simultaneously, because Mary’s voice is nowhere to be seen in the historical record, it is hard to ascertain her desires. While we can assume her desire for freedom, we do not know her relationship to John Hylas and whether his legal authority to claim her offered her a pathway to freedom that was safe or of interest to her. Notably, British law recognized her consent neither as a married woman nor as an enslaved woman. Historian Katherine Paugh highlights this, illuminating the legally complex status of women like Mary Hylas, enslaved women, in the 18th century. She uses this case to critique the limited scope of British abolitionist reformers, arguing that this case demonstrates their continued commitment to the subjugation of women through marital law, going as far as using it as their core argument against Mary Hylas’s enslaved status. Unlike the American institution of slavery, which had ruled out the compatibility of slave status and legal marriage by this time, Britain had not, leaving a complex legal knot about the relationship between the two.

Nonetheless, Hylas v. Newton provided precedent in the British legal system that Judges sought to suppress in other legal cases, including the landmark court case Somerset v. Stewart.

Thomas Lewis: Lewis v. Staypleton

Another (supposedly) enslaved man, Thomas Lewis, benefitted from yet another loophole. In 1770, retired captain Robert Staypleton claimed ownership over a Black man named Thomas Lewis and arranged for his abduction for sale to slavers headed for Jamaica. They almost to abduct Lewis, who screamed loud enough to draw enough attention that the servants of wealthy onlookers, but the henchmen claimed to have a magistrate’s warrant for his arrest, leading the servants to retreat for fear of their own arrest. They bound and gagged Lewis and loaded him onto a boat, sailing him down the Thames to a larger ship Jamaica bound. Lewis’ salvation came as a result of his screams, which were overheard by Mrs. Banks, the wealthy mother of famous botanist Joseph Banks, who immediately contacted Granville Sharp for his assistance in the matter. Sharp dove into the case headfirst, demanding an injunction for Lewis’s return, even though the ship had already departed. Thankfully, bad weather had delayed the voyage and forced the ship to temporarily dock in Kent, allowing Lewis to be rescued. A court case ensued wherein Sharp sought to prosecute Staypleton for assault of Lewis, which the defense argued was the former’s right as Lewis was his property. Because of his reticence to make a definitive claim about the legality of slavery (which he frequently avoided), the presiding Judge Mansfield directed the jury to deliberate over whether Lewis was indeed enslaved, not whether slavery was permissible or what a slave owner had rights to do to his enslaved property. In an unexpectedly fortuitous twist of fate, Lewis won his freedom on this technicality as Staypleton could not produce proof of purchase.

As with Hylas, Lewis’s voice is silenced by the racial subjugation of the time, repeated in the violence of the archive, so we do not know anything of his experiences throughout this trial and what he thought of the outcome. But we do know that he dared to challenge the status quo and hope for more than British law allowed in the legally ambiguous status of enslavement.

James Somerset: Somerset v. Stewart

James Sommerset, of the Somerset v. Stewart trial of 1772, served as a key actor in British abolitionism, so let us consider the case from his perspective. Somerset, a Black man enslaved in British Virginia, was torn from kin and family by his enslaver, Mr. Charles Stewart, in 1769. Somerset endured enslavement in England until 1771, when he fled his master and refused to continue work as Stewart’s enslaved property. Although Somerset’s thoughts and feelings are unknown, we do know that in London, he would have encountered lots of free Black people working in the bustling city, and it is likely that seeing these possibilities made him question why his lot differed so much. He would have also seen the free Black presence in London as a perfectly busy setting into which he could anonymously slip and build a free life. Sadly, Somerset did not get very far. After only a few months of self-made freedom, slave catchers viciously rooted him out, captured, chained, and imprisoned him on board a ship on the Thames, and threatened him with deportation to Jamaica for his crime of self-stealing. Somerset found aid through his religious family, godparents, and abolitionists who secured a writ of habeas corpus on his behalf, meaning he would have his day in court.

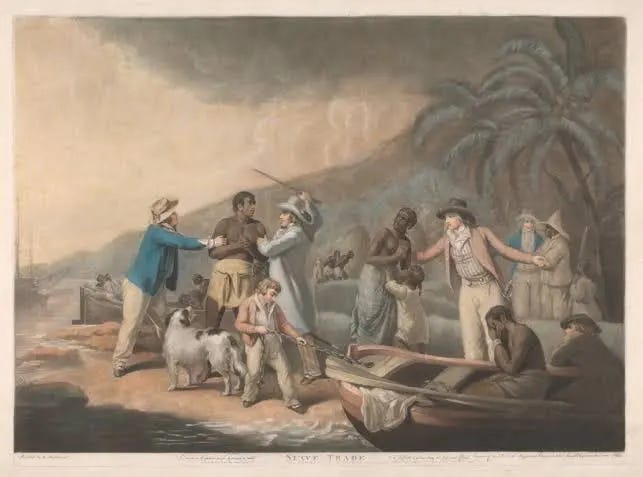

“The Slave Trade” by John Raphael Smith (1791). Credit: Yale Center for British Art, accessed via: Lincolns Inn

Somerset and his allies secured support from legal scholar, abolitionist, and philanthropist Granville Sharp, who had long-awaited an opportunity to support another court case in the name of abolition. Sharp eagerly took the case and enlisted three other anti-slavery barristers to partner with him on the case. Both men saw Somerset’s case as an opportunity to mount a challenge against the existence of slavery in Britain. Nonetheless, the odds were not in their favor. In the eyes of Judge Mansfield, the injured party was Somerset’s enslaver, Stewart, agreeing with the former’s affidavit that claimed Somerset had “departed and absented himself” from service, depriving Stewart of his property. In court, the defense attempted to sidestep the question of slavery’s morality and argued that for the court to deny Stewart’s property rights (simply because he had travelled to Britain on business) would be damaging to British commerce, suggesting that it would lead to the abolition of slavery and losses of multiple hundreds of thousands of pounds. While this seems a relatively weak argument to us in the 21st century, this was the centerpiece of the British pro-slavery argument in the 18th century, as commerce in the British West Indies was the backbone of the British economy. Additionally, this was the only basis of appeal in a nation where slavery had no explicit legal terms.

In defense of Somerset, Sharp and the prosecution centered their arguments on much of Sharp’s longstanding research into the legal history of slavery in Britain. They argued the proposition that “no man in this day, is or can be a slave in England,” a longstanding legal opinion that they believed required “the introduction of some species of property unknown to our constitution.” They highlighted that slavery only existed in colonial law; meanwhile, Britain had never legally sanctioned slavery, and thus the protections offered by British law applied to everyone, evidenced by Judge Mansfield’s willingness to grant Somerset a writ of habeas corpus.

As one of the chief architects of British commercial law, Judge Mansfield had dreaded and dodged ruling against the legality of slavery for decades, and he employed many tactics to avoid reaching a verdict in this trial, too. He attempted to persuade Stewart to drop the case and simply free Somerset, or to negotiate and settle out of court. He repeated this request more than three times, and even petitioned one of Somerset’s abolitionist supporters, Elizabeth Cade, to purchase him from Stewart and free him herself, which she refused to do. Mansfield also repeatedly adjourned the case and delayed proceedings, forcing the trial to move at a stuttering pace between December 1771 and June 1772. This tactic ultimately worked against him, allowing Sharp and his team to shore up their argumentation and for journalists to stoke public interest in the case. What Mansfield hoped would be another suppressed runaway slave case transformed into a landmark case that shook the nation even before his verdict, pushing discussion of freedom, slavery, and property into national discourse.

Over a month of deliberation, Lord Mansfield weighed the costs and consequences of ruling for or against Somerset. In June 1762, the judge entered an overflowing courtroom filled with journalists, abolitionists, those with vested interests in Caribbean commerce, and curious onlookers, to deliver his verdict. He argued that Stewart’s kidnap of Somerset was so “high an act of dominion,” that it could only be seen as permissible if it was a right “recognized by the law of the country where it is used,” judging that slavery required “positive law, which preserves its force long after the reasons, occasion, and time from whence it was created, is erased from memory.” He went on to argue that slavery was “so odious, that nothing could be suffered to support it, but positive law.” Therefore, according to Lord Mansfield, whatever the consequences, he must rule that “the black man must be discharged.” Somerset was free, and finally, Britain had a court ruling that had not rendered Black freedom a loophole and individual success, but instead definitively declared slavery’s end on British soil.

The court did not allow Somerset to speak in his own defense, seemingly rendering him a passive recipient of justice and freedom. However, this is untrue. Somerset’s success in this case depended upon his sustained determination to reach freedom and his ferocity of will. Though the record is silent on it, no doubt Somerset lived in danger for the long duration of the trial, with threats of violence and kidnapping marking his life. Yet, he persisted, fueling Granville Sharp and his team’s dogged pursuit of the end of slavery on British soil. This case, in particular, demonstrates the centrality of enslaved people to abolitionism, despite their invisibility in the record.

Black celebrations began immediately after Lord Mansfield uttered his verdict. Newspaper sources describe that Black onlookers in the courtroom rose and:

“bowed with profound respect to the Judges, and shaking each other by the hand, congratulated themselves upon their recovery of the rights of human nature, and their happy lot that permitted them to breathe the free air of England. – No sign upon earth could be more pleasingly affecting to the feeling mind, than the joy which shone at that instant in these poor men’s sable countenances.”

Slavery’s End?

The ending of slavery on British soil served as only one battle in the war to end Britain’s continued commitment to slavery. Slavery still existed in the British Caribbean, and Britain remained a frontrunner in the Transatlantic Slave Trade. Black abolitionists continued to ally with white abolitionists to eventually deal a death blow in these remaining battles. Come back soon for an exploration of some of those Black activists.