One Year In: Church, Who Will You Be?

MLK's Sustained Challenge to the Church

A year ago, Dr. Reverend Martin Luther King Day coincided with Inauguration Day. I remember feeling it to be a cruel irony that read as a sign, some kind of prophetic warning. A national holiday where many reflect on the unthinkable sacrifices made by Black citizens (and their comrades), people who suffered centuries-long violence at the hands of their fellow countrymen and the State. A people who gave more than should have been required to prove that there is abundance. The inauguration of a candidate whose platform denied and sought to write these violences out of the American narrative, while pledging a deluge of blessings upon the nation in simple exchange for the marginalized and the vulnerable. A people who have taken much to tell us that there is not enough to share.

Perhaps this moment revealed the Janus face of the nation, the unholy congruity of incongruous things. Perhaps it was the timely elucidation of divergent characters we can choose to embody: sacrifice for the collective good, or excuse harm for self-preservation.

However you slice it, what a cosmically meaningful collision.*

There are few moments where the strictures of time can so artfully paint such moral conundrums so clearly. To me, it felt like an existential test, or a fable through which your whole worldview is challenged. To me, it felt almost Biblical.

It reminded me of the Israelites at the end of Joshua’s life and leadership, once again presented with a choice: continue to serve God (who had been faithful and good), or the gods of the Amorites (who felt proximate and seemingly powerful). Joshua said:

... choose you this day whom you will serve; whether the gods which your fathers served that were on the other side of the flood, or the gods of the Amorites, in whose land ye dwell…

(Joshua 24:15).

January 20th 2025, posed that very question. Put another way: “Who will you be? Whose power will you submit to?” And a year on, as the nation descends into increased state violence, the normalization of hatred of enemies, made worse by encouraged scorn for the most vulnerable, we must ask: “Who have you been this past year? And whose power have you submitted to?”

For Christians living in our respective Babylons,** these questions are both individual and corporate: Who have we been as the Body of Christ, both locally and nationally?

I am blessed that locally I can rejoice for the appendage of the Body of Christ that He has placed me in. We have rejoiced together and lamented. Leadership has encouraged us to remain in Christ with our hearts and minds stayed on Him as He leads us in the right response to the cultural moment we are in. I have seen the needy provided for and the vulnerable protected. I have seen leadership encourage congregants to find their position and play it well, and instruct us to love, even when it is hard. Here, loving our enemies is not an option but a mandate. Consistently, we are reminded and challenged to be Jesus’ disciples at all times and in all ways.

Now, I begin here to highlight a truth that often gets drowned out by the loudest in our ranks: countless churches are continuing to do the faithful work of Christ, equipping the saints to faithfully engage this climate. I do not, and cannot, believe mine is exceptional. I pray for these congregations often. However, it is also true that when I think of the loudest “Christian” voices right now, and how they have stewarded the masses, my heart is filled with despair.

Let’s turn to history to name this despair and to answer the questions.

First Lesson from A Letter: Who Will We Be?

In January and April 1963, Birmingham, AL, an eccumenical and interfaith group of white ministers and rabbis came together to denounce the presence of Martin Luther King and the marches and sit-ins planned by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, as “untimely and unwise.” While accusing MLK of being an “outside agitator” and deeming the nonviolent activists as breeding anarchy and violence, they commended “the community as a whole… and law enforcement officials in particular, on the calm manner in which these demonstrations have been handled,” and for “preventing violence.” We stand over 60 years later with almost canonized images of police dogs ravaging protesters, police clubs breaking bones of men, women, and children, and fire hoses tearing clothes and skin. Violences that are rendered invisible and irrelevant by the clergy who lived among the violence and its fallout.

Police dogs set upon a man during an anti-segregation demonstration in Birmingham, Alabama, 1963. Accessed via, Reuther Library.

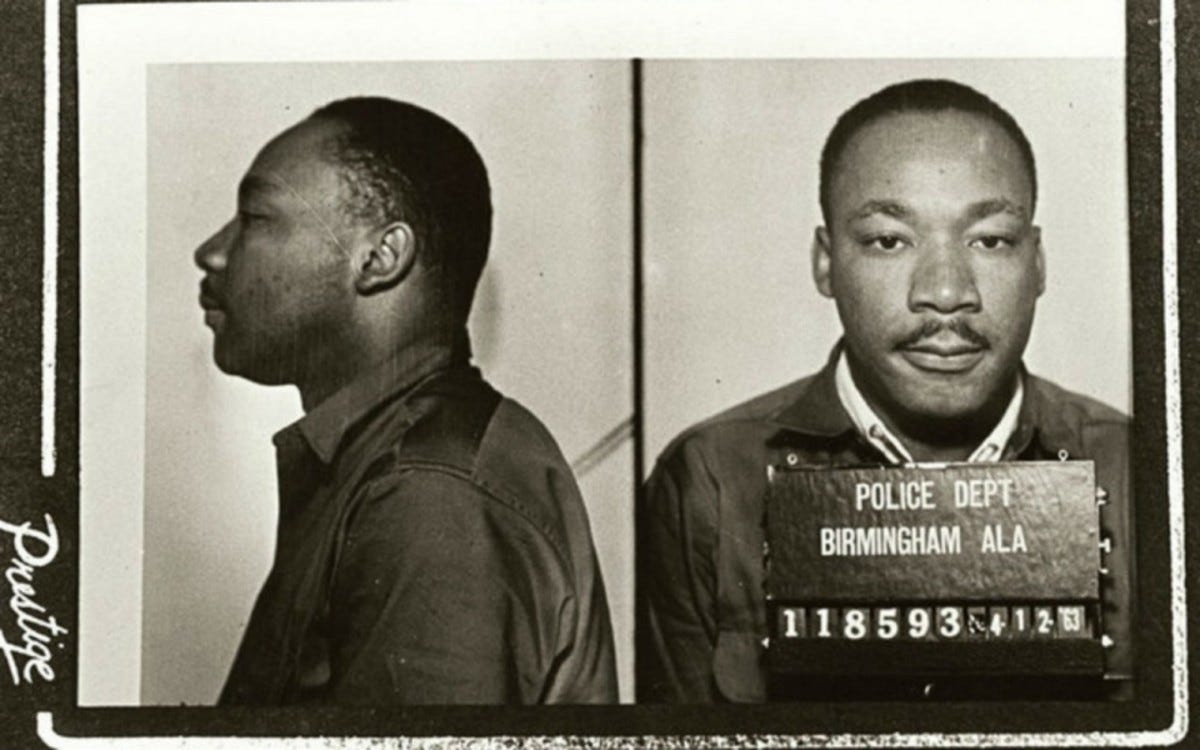

These statements are the oft-forgotten cause of Martin Luther King’s most famous piece of writing: A Letter from a Birmingham Jail. Penned after his arrest by Birmingham police following a peaceful protest in the summer of 1963, King found himself imprisoned with time, energy, and cause to respond to the accusations of his brothers in the faith. The sections of MLK’s letter that outline the many errors of his accusers, particularly the failures of the Church, serve as prophetic warnings to us about the importance of deciding who we will be in the face of injustice. It serves, too, as a salve for the disappointed. He wrote:

I have been so greatly disappointed with the white church and its leadership. Of course, there are notable exceptions… But despite these notable exceptions, I must honestly reiterate that I have been disappointed with the church. I do not say that as one of those negative critics who can always find something wrong with the church, I say it as a minister of the gospel who lives the church, who has been nurtured in its bosom, who has been sustained by its Spiritual blessings, and who will remain true to it as long as the cord of life shall lengthen.

King goes on to express his expectation to have the support of the white church in the fight to end segregation, only to find many

outright opponents, refusing to understand the freedom movement and misrepresenting its leaders; all too many others have been more cautious than courageous and have remained silent behind the anesthetizing security of stained glass windows.

An unlikely salve, but knowing that the Church has been here before freed me from the straitjacket of fear that tells me the church is somehow falling apart in a new way, rather than the reality that we are seeing the unhealed boils of injustice (as King terms it) exposed again. I could unpack this despair more, but I think many of us are familiar with it. Countless have left their churches and lost relationships; others have lamented seeing those they call brother and sister abandon the central tenets of the faith; many have walked away from God altogether, struggling to disentangle Him from the web of deceit and earthly power that many have spun around Him. We have watched the Bride of Christ willingly tear her gown for a lesser groom. We must, as King did, lament that disappointment thoroughly and constantly.

The sections of MLK’s letter that outline the many errors of his accusers, particularly the failures of the Church, serve as prophetic warnings to us about the importance of deciding who we will be in the face of injustice.

But I want to focus on the prophetic warning that rings through time from King’s pen to this moment, as it helps us answer the question “who will we be?” Heed the warning: in this iteration of Babylon, we must take care not to be “more cautious than courageous,” and not to “remain silent,” allowing the security of our sanctuaries, our perceived set-apartness, to anesthetize us from following the commands of Jesus in, and for, the broken world around us. Much like in the Civil Rights era, many leaders mistake compliance with the status quo and preservation of false peace as the way forward. This is a deeply consequential mistake, illuminating allyship to the world over Christ.

We must be wise to know when action is required of us, and when false peace is masquerading as the real thing.

We must not comply with evil regimes that subvert the commands of God.

We must not caution ourselves out of doing good.

We must not caution ourselves out of being courageous.

We must not caution ourselves out of obedience to Christ, trusting more in the powers of this world than in the One, True God.

Similarly, we must not remain silent. Proverbs 31:8-9 commands us to “speak up for those who cannot speak for themselves, for the rights of all who are destitute. Speak up and judge fairly; defend the rights of the poor and needy.” Silence is not an option for the people of God, nor is speaking up an added extra. Nor is it something the needy must earn from us. Indeed, in our self-righteousness, many of us demand blamelessness from the people Jesus calls us to protect. Perhaps this is why Paul reminds us frequently to remember who we were, to remember our sin and confess often, so that when we behold our neighbor, we have the humility to see our own neediness in theirs.

A protester is detained by Federal agents near the scene where Renee Good was fatally shot by an ICE officer last week, Tuesday, Jan. 13, 2026, in Minneapolis.(AP Photo/Adam Gray), accessed via, KRCTV.

Second Lesson From a Letter: Who Have We Been This Year?

As I think on these questions retrospectively, “Who have we been this past year?” MLK’s evaluation of the church in 1963 sings in uncanny harmony with my answer. He wrote:

So here we are moving toward the exit of the twentieth century with a religious community largely adjusted to the status quo, standing as a taillight behind other community agencies rather than a headlight leading people to higher levels of justice.

I have wept over the laxity of the church. But my tears have been tears of love.

Through a thorough critique of Christian activism in the 2020 era, the Church, by and large, has relegated “social justice” to the secular world, rendering it a four-letter word to those who want to be seen as “serious” and sound Christians. Thus, where MLK saw a Church “largely adjusted” to the status quo, I see one that is not only adjusted to the cruelties of the day but defending and sanctifying it.

Where he saw the Church as a taillight behind others in the pursuit of justice, I see the Church acting as the brake lights, actively holding back justice.

Where he saw the Church as lax, I see the Church losing her sight, being led about by those she has put her trust in, to do what she would never do with clear sight.

This is not to say our moment is worse than that of the horrors of Jim Crow or slavery, but rather to say that sin unrepentant begets sin, growing in us like a cancer. At best, it simply stays within us, rearing its ugly head here and there. But at worst, it overtakes us and embeds itself in our very nature. This is why compliance and compromise is dangerous. It will define the character of the Church.

Much like in the Civil Rights era, many leaders mistake compliance with the status quo and preservation of false peace as the way forward. This is a deeply consequential mistake, illuminating allyship to the world over Christ.

I fear that the last year has altered much of what it means to be a Christian in America. The powers that be have sought to rewrite the Gospel of Jesus and tell us who He wants us to be. They present themselves as apocryphal texts that offer a greater revelation, permitting us to abandon the teachings of Jesus. They twist scripture as the devil did when He tempted Jesus in the desert, but I fear that where Jesus beheld fasted-clarity of the truth, we are over-stuffed and too glutted for earthly power to discern the truth as He did.

A Time to Choose

Perhaps MLK was more gracious than I. In fact, I’m certain that this is true. Nonetheless, I do not write this with pride in my chest; I know that I am not free from these same trappings, and I am part of this same Body. But I do write with tears of love for my brothers and sisters, sighing out a prayer as I lament who we have been, and pray for who we will be in this cultural moment. I pray that soon and very soon, we will fall on our knees and ask forgiveness for bartering away our inheritance, and for a deeper knowledge of His love and His will. I pray that we will remove our blessing from the status quo and actively challenge it.

Mugshot of Martin Luther King Jr following his 1963 arrest in Birmingham, accessed via: WikiCommons.

May we remember who Christ called us to be. And may we have the courage to be that.

Let me close with my version of Dr. King’s closing words in his letter:

If I have said anything in here that overstates the truth and indicates an unreasonable evaluation, I beg you to forgive me. If I have said anything that understates the truth and indicates my permitting anything that allows us to settle for anything less than being the true Bride of Christ, I beg God to forgive me.

*By “cosmically,” I mean the collision of two wildly different worlds and worldviews, the collision of the Spirit of sacrifice with the carnal flesh that devours. To me, it is a picture of the wheat and the chaff, or of the defeated powers and principalities raging on like they could still win.

** By “Babylon” I am drawing from Dr. Preston Sprinkle’s terminology that encourages us to understand ourselves, the Church, as “exiles in Babylon,” rather than the often pushed “Christian nation” narrative. While many find this daunting or perceive it as a failure of the Church, I believe it is a more freeing status that allows us to divorce worldly power; see the functions of the nation more clearly; understand our faith more accurately as a global, multiracial, and multicultural one; and faithfully rely on the power of God and God alone.

References:

Martin Luther King Jr., A Letter from a Birmingham Jail

Alabama Clergymen’s Letter to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr

Preston Sprinkle, Exiles: The Church in the Shadow of Empire

This reminds me that I am a believer in-spite of Christians not because of them. Because of Jesus not because of people who say they follow him. It's so hard to keep this focus, but I remember that God is coming for a remnant not an abundance. I pray to remain a remnant