Myth-Busting Black British History: “Black/African People Have Not Been in the UK very long!”

Part 2: Tudor England to World War I

Welcome back to the whirlwind synoptic history of Black people in, and in connection with, Britain. There is a lot to cover so let’s get straight into it!

Black Tudors and the Early Modern Mind

Beyond the European imagination, Africans found their way to English and Scottish lands, becoming more visible in the Early Modern era of Tudor England. Because Portugal and Spain instigated and dominated connections with Africa, and the early Slave Trade, historical records suggest that many of the Africans who arrived in Tudor England came via Europe. In particular, those in servitude during the reign of King Henry VIII likely came as part of the court of Catherine of Aragon. Throughout the Tudor era, Africans could arrive in England as anything from ambassadors of African nations to enslaved people, demonstrating that the rigid association between African ethnicity and slavery had not quite taken root.

This is particularly clear in the story of Tudor Trumpeter John Blanke (or Jean Blanc). Blanke served in the courts of Henry VIII from roughly 1507 to 1512, and he is known as a man of African descent, likely from North or West Africa. Though his origins are relatively unknown, his race is known because of visual records from the time. The Westminster Tournament Roll, a 60-foot-long document that depicts an extravagant jousting tournament held by Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon in celebration of the birth of their son. A two-day event marked by music, pageantry, and jousting in which the King himself took part, the roll depicts John Blanke, the first named African in Britain’s record. Blanke is featured twice as a heralding trumpeter, alongside white trumpeters. This is definitive evidence of a skilled Black man not simply living in England, but also embedded in the King’s Royal Court, a reality unimagined by most who have learned about the Tudors.

John Blanke as featured on the Westminster Tournament Roll, accessed via the National Archives.

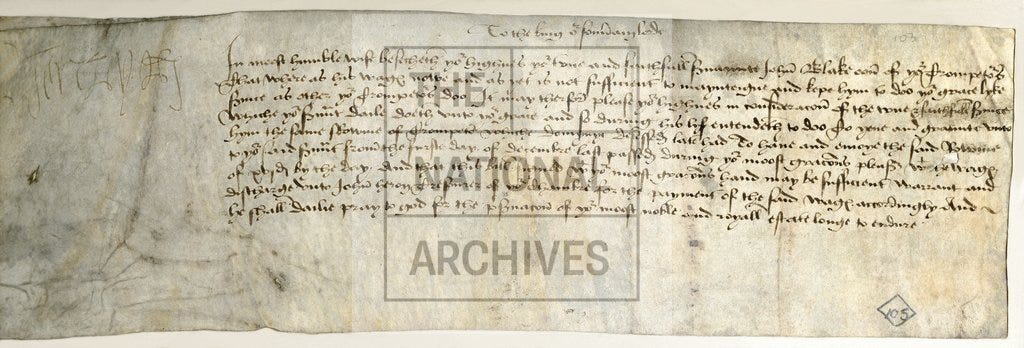

Not only is there a visual record of John Blanke, but we are also able to know more about his life thanks to the preservation of written correspondence between him and the King. In a bundle of letters now held at the National Archives in London, there is an undated petition to the King, written by John Blanke, requesting an increase in pay from 8 pence per day to 16 pence. While for many it may be striking that Blanke was paid at all, I am particularly astounded by his request to be paid the same as his colleagues, including back pay for the months he’d served so far. From this request, we can see that not only was Blanke being paid less, possibly on account of his race, but we can also see his boldness that demanded equal treatment. Though the record is isolated to Blanke’s experience, this suggests some of the racial dynamics at play in Tudor England.

Blanke made the argument that this pay raise could be accomplished by promoting him into the role of another trumpeter who had recently died, and historians believe that his confidence came from a positive relationship between him and the King. This certainly seems to be the case as King Henry approved his request. John Blanke lived as a skilled worker in the courts of the King, seemingly married to an Englishwoman, and was able to negotiate his salary. Each of these defies the presumption of enslaved status being the only status available for Africans in Tudor England.

John Blanke’s petition to Henry VII, accessed via the National Archives.

Historian Miranda Kaufmann explores the history of Black Tudors in her seminal work Black Tudors: The Untold Story, which I will be giving away to one lucky reader at the end of the month!

Black Victorians

Because I intend to cover the Transatlantic Slave Trade in the next post, let’s skip ahead to the Victorian Era.

Britain abolished slavery in 1833, and the Victorian British narrative transformed abolitionism from a fringe activist concern in the UK into part of British identity and moral character. This led to many Brits taking part in abolitionist efforts across the world. Indeed, the Crown deployed British ships named “The West Africa Squadron” to the coasts of West Africa to intercept slave ships and liberate enslaved people. While they only succeeded in intercepting 6% of slave ships, 150,000 men, women, and children were liberated between 1808 and 1860. These seamen transported many of these liberated peoples to Sierra Leone, where some settled in Freetown, while others were recaptured for enslavement or forced into the army. To this day, those descended from those who settled in Freetown celebrate the “re-captives” who were rescued from a lifetime of enslavement, describing them as “the lucky ones.” However, these valiant efforts over time merged seamlessly with British colonization efforts on the continent.

Meanwhile, African and Caribbean descended people, both former slave and free, continued life as part of British society. While Black communities were not widespread across the nation, Black communities were small and concentrated in locations of available labor, particularly near the docks of Liverpool and Cardiff, or in the hubbub of metropolitan London. Many African elites took advantage of connections with the UK and arrived for schooling or to work as traders between Britain and their home nation. Formerly enslaved people from America and the Caribbean also sought settlement in Britain, hoping to benefit from the freedom on offer. As a result, Black Brits of the Victorian era spanned all classes, from domestic workers (who made up the largest group) to those who worked as part of the Royal Navy or as merchants. Despite varied class positions, racism marked work and life in Victorian Britain. Many white families who used Black people as domestic laborers saw fit to treat them as “slave servants,” subjecting Black men, women, and children to violence and maltreatment. In the Royal Navy, Black men reported unequal treatment and a stagnation that prevented them from rising through the ranks.

One exceptional story is that of Sara Forbes Boneta. During negotiations between Dahomey and British traders, the Dahomey, reluctant to end the slave trade, offered a young girl as a “gift” to Queen Victoria. Despite the mission of the West Africa Squadron to end enslavement, Captain Forbes takes the “captive girl” and other gifts back to England, renaming her Sara Forbes Boneta. The young girl was aged 6 upon her arrival in 1850. Queen Victoria recorded in her diary that Boneta knew English (which demonstrates the “creolization” that took place in coastal port cities). It is likely that she learned from exposure to British merchants and had been raised with this fate in the mind of the Dahomey Royal Court. Queen Victoria described her as intelligent and smartly dressed, but remarked upon her “woolly head and big earrings,” giving her “the negro type,” hidden initially by her bonnet. She became the ward of Queen Victoria, making her a woman of great privilege. Simultaneously, Sara was forced to live with the reality of being used as an experiment to prove that British paternalism could civilize Africans.

Portrait of Sara Forbes Boneta, accessed via Post News Group.

Unlike John Blanke three hundred years prior, intermarrying with the English aristocracy or any other white English person was unthinkable, and so she was married to trader James Davies from Freetown, Sierra Leone. In fact, Davies was the child of enslaved people freed by the West African Squadron. In this picture, and others, we can see the fusion of African and British identity in Sara, revealing that the “becoming something new” goes way back in time. While Boneta is exceptional in her unique experience as a Black ward of the Queen, much of her complex identity formation can be imagined as a common experience among the many Black Victorians living in Britain.

The late 19th century brought the Scramble for Africa, which transformed the relationship between Africa, the Caribbean, and Britain. In fact, because this served as the turning point that has defined the subsequent presence of Black people in the UK, that will have its own post, too!

World War I

Let’s close out with World War I. By 1914, the outbreak of the war, Britain had the largest colonial empire in the world, with colonies on every continent. If that scope does not capture the expansiveness of the British Empire for you, know that more than ¼ of the world’s population was under British colonial rule at some point in history. This is an important backdrop that we must acknowledge before we discuss World War I, as it is essential to the name itself. Growing up, I always wondered why the wars were called “World Wars” when they were mostly fought in Europe, between Europeans, with American input. The history is demonstrated in the name: Britain had colonized much of the world and therefore, the First and Second World Wars embroiled the Empire, too, including Black military service.

Portrait of Alhaji Grunshi, accessed via The Bay Museum.

In fact, public historian David Olusoga argues that “the First World War began in Africa.” In the then-named “Togoland,” Black soldier, Alhajii Grunshi of the British West African Frontier Force, fired the first shots of the British in the war. This extraordinary and untold moment perfectly demonstrates the shift in the relationship between Black people in the UK and across the Empire, and Britain. Over the course of the war, the Crown enlisted one million Africans to work as carriers for the army, roughly 100,000 of whom were killed in battle (some estimate that figure as an underestimation of 50%). Those who served in the military came from all over the continent: many from Sudan, Rhodesia, Ethiopia, and Nyasaland formed regiments under the King’s African Rifles; Ghana enlisted thousands of men into the Gold Coast Regiment, fighting in East Africa; the West African Frontier Force comprised of Nigerian soldiers. Olusoga argues that at the beginning of the war, and upon encountering one another from differing British colonies, African soldiers had hope in their unity and that their service would demonstrate Black valiance and capability. Most importantly, though, Africans and Caribbeans at this moment believed colonialism to be what the British said it was: an extension of British citizenship, and so, many sought to demonstrate loyalty to “their nation” and “their Crown.” However, racism marked the experiences of these soldiers who faced lesser rations, insufficient and lower-quality clothing, and supplies. By the end of the war, those who survived returned to their nations filled with discontent and disillusionment.

West Indian regiments had similar experiences. At the outbreak of war, many were eager to take part, and men from the Bahamas, Grenada, British Honduras (now Belize), British Guiana (now Guyana), the Leeward Islands, St. Vincent, Barbados, Trinidad and Tobago, and Jamaica all sought to serve as soldiers, auxiliaries of the British Army. In towns across Jamaica, impassioned people held rallies in support of the war, and newspapers debated the threat of German invasion, fueling a “pro-imperialist euphoria” among the people. This rampant patriotism came from the high esteem those in the British Caribbean had for the then recently deceased Queen Victoria. They saw the Queen as an emancipator of sorts, as she ascended to the throne shortly after Parliament passed the emancipation acts in 1833. This fostered a sense of goodwill and loyalty that survived and served Britain’s war effort. Unsurprisingly, Britain took advantage of this wave of patriotism, using it as evidence of Jamaica as a “paragon of morality and virtue,” evidence of their successful “civilizing mission,” in great contrast with “German tyranny” and brutality. Eventually, in May 1915, the Colonial Office approved the formation of a West Indian regiment.

Image of the British West Indian Regiment doing much of the grunt work reserved for Black soldiers. They spent time digging trenches, building roads and gun emplacements, acting as stretcher bearers, loading ships and trains, and working in ammunition dumps. Accessed via: Imperial War Museum.

Throughout the war, Caribbean regiments fought in Egypt and the Middle East because the British believed that they would be better equipped to handle the heat than white British soldiers. African, Caribbean, and the million Indian soldiers who fought, too, faced racist mockery and maltreatment at the hands of the British. Many military superiors mocked the idea of Black people’s capability to serve in the army, and one Trinidadian soldier reported that he and his Black comrades were “treated neither as Christians nor as British citizens, but as West Indian ‘N*ggers,’ without anybody to be interested in or look after us.” The army actively withheld promotions from Black soldiers, making every effort to ensure the army reflected the racial hierarchy of the day. The experience of such treatment at the hands of white British superiors brought an end to any belief in a British citizenship or a “free empire” that extended throughout the colonies. Instead, Africans and Caribbeans left the war with anti-colonial sentiments that would mark the 20th century.

Though these are not Black British men and women in the sense of those born and raised on British soil, the British, through its Empire, expanded British soil to these territories abroad. Therefore, these stories and experiences are central to British history and our understanding of how ideas of race and racism functioned in the early 20th century. Further, these are the stories of the ancestors of Black British people, no matter our arrival date.

A New Timeline

Although this is a whirlwind narrative of the history of Africans and Caribbeans in connection with and living in the United Kingdom across time, I hope that it demonstrates the long history that must be studied and celebrated. There is not one Black British story, much like we are not a monolithic people group today. Examining these many moments in time illuminates the number of stories that we still have to explore to get a fuller picture.

—Come back next week, when we will discuss the final (and most pervasive) myth I need to bust: “Slavery didn’t exist on British soil!”