Myth-Busting Black British History: “Slavery Didn’t Exist in the UK!”

Part 2: Britain and the Transatlantic Slave Trade, on British Soil and Beyond

In the previous post, we established the origins of the myth and the flexibility of both racial classification and enslaved status in the early 17th century. Now let’s get into the real history of Britain’s activity in the Transatlantic Slave Trade and explore the ways it instigated another wave of Black settlement in the UK.

Proof of Racialization

Historian Olivette Otele argues that the 17th century can be characterized by changes in how Europeans perceived Africans, and this is evident in Britain. Upon establishing the British slave trade, Blackness quickly became associated fully with Africanness and subsequently enslavement. We see this most clearly in Elizabethan English plays, like Othello, where Blackness is depicted as evil, foolish, hypersexual, and untrustworthy. Otele highlights that “Black heroic characters in England were flawed,” with Othello imagined as a man riddled by jealousy to the point of murderous rage, character traits intended to point to his Blackness and Muslim religious identity. Similarly, Shakespeare’s racialized construction of Othello suggests a deep attachment to duty and service, highlighting Black usefulness. It also implies that, despite incorporation into European ways and culture, Othello remained too African to be European. Contrastingly, Spanish stage depictions of Blackness centered more on stupidity and enslavement. In both constructions, though, analysis of plays and popular culture of 17th-century Europe confirms the proliferation of negative stereotypes regarding Black people.

This is an important cultural backdrop that helps us understand the world of ideas that British people encountered and entertained, as well as the world Africans stepped into upon their arrival in Britain. These views fueled the Transatlantic Slave Trade, serving as justification of for the brutality and violence wrought on Black bodies, as well as their sale.

Britain and the Triangular Trade

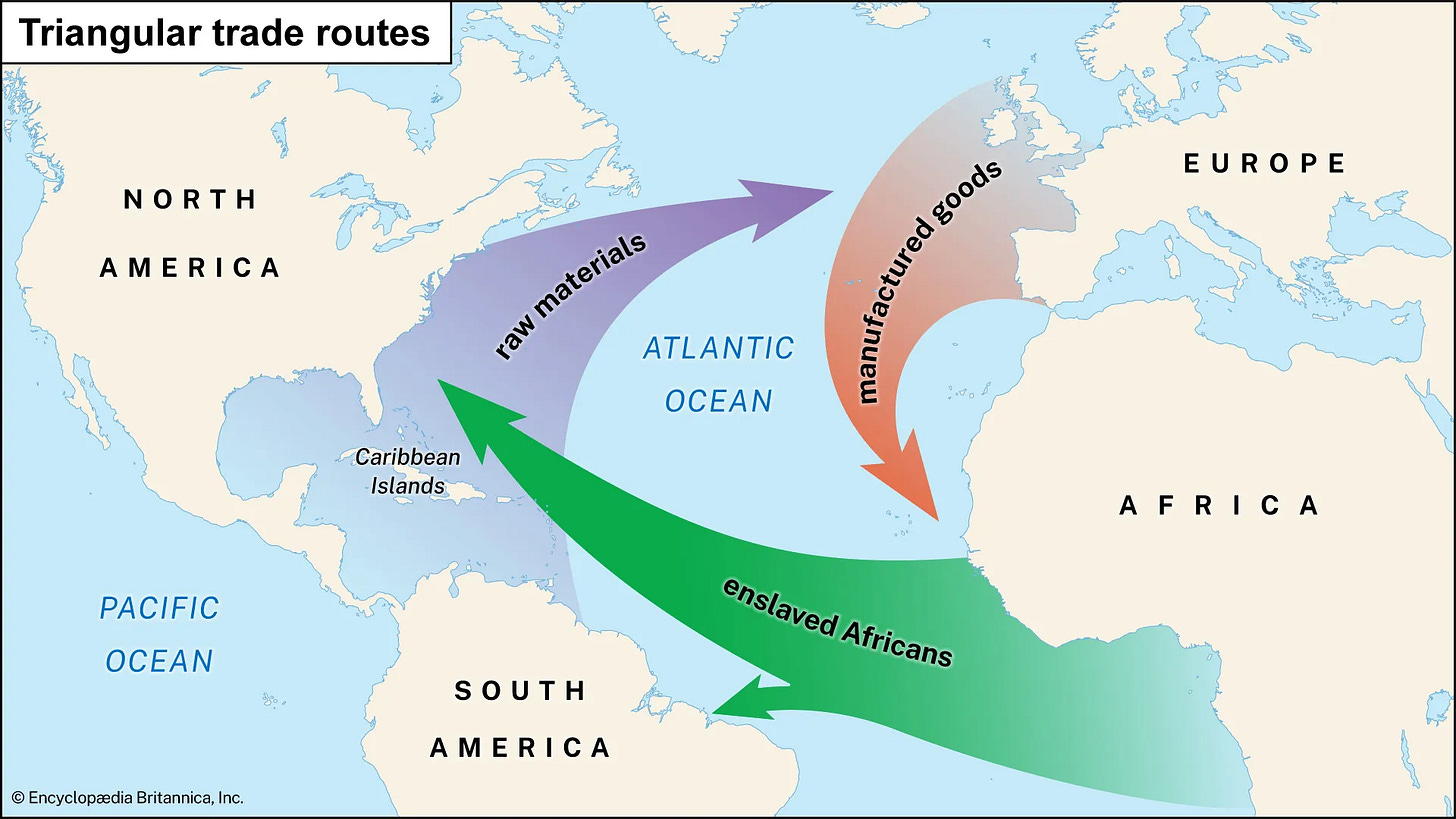

Beginning in 1562, Britain fought to establish slave trading ports and castles across the coasts of West Africa, attempting to break the monopoly on the trade by the Portuguese. Despite initial challenges, Britain succeeded in joining the Transatlantic Slave Trade, quickly taking root as one of the most dominant nations in the trade. Over the course of two and a half centuries, Britain transported over 3.5 million Africans across the Atlantic, a route known as the “Middle Passage.” Slavers and sailors engaged in brutal acts of violence, from sexually assaulting Black women onboard and in the castles before departure, brutally whipping and branding men, women, and children, and keeping the hundreds of enslaved people chained together in dungeon cellars built for tens of people. Off the coast of Sierra Leone on an island called Bunce Island, the remains of a British slave castle are still visible. On that island, English traders bartered with local elites and other European traders for the sale of human flesh. The remains today include the area of auction and sale, as well as quarters assigned for the assault of enslaved women. This illuminates that the horrors of enslavement took place even before enslaved Africans reached the Caribbean, Americas, or Britain.

Illustration of the routes taken by merchants in the “triangular trade,” accessed via: Britannica.

For two centuries, enslaved people in the Caribbean cultivated sugarcane, from planting to harvesting to processing, on plantations throughout the Caribbean islands. As slavers and merchants took the cultivated sugar and sold it back in the British metropole, they realized fortunes could be made and pushed for the acceleration of the slave trade (hence the term “triangular trade”). Here economic driving forces sped down the already worn path of racialization, by which Europeans argued that Africans were suited both to the heat and humidity of the Caribbean, and to the hard labor required for sugar cultivation. By the end of the 17th century, the Black population in the Caribbean rose dramatically from 20% in the 1650s, to 80% by the early 18th century.

“Planting the Sugarcane,” by William Clarke, 1823, depicts slavery in Barbados, accessed via: Encyclopedia Virginia.

Enslaved people who survived the horrors of slave castles on the African coasts and the brutality of the Middle Passage had been initiated into a new world of normalized extreme racial violence. Historians estimate that the journey through the Middle Passage claimed anywhere between 12% and 25% of enslaved Africans. Upon their arrival to the Caribbean islands, slave traders prepared their human cargo for sale by washing and oiling them to make them appear healthy to local buyers. In these sales, families were separated and English buyers sought to strip enslaved people of their individuality and culture by replacing their native dress with coarse, shapeless clothes and renaming them monosyllabic English names. By the mid-18th century, the Transatlantic Slave Trade guaranteed a steady supply of enslaved people into the Caribbean because the harsh labor and treatment of the enslaved led to a high death rate. Not only were enslaved people beaten and tortured by overseers, but the labor itself also endangered them due to fire and boiling water required to process sugarcane into sugar.

Although this is not an account of enslaved people brought to live and work in the UK, it is still central to Black British history. The booming trade of enslaved people, sugar, rice, cotton, indigo and more, by English traders became the backbone of the British economy and fueled the Industrial Revolution. Cotton from North American colonies was taken back to England and used in the booming factories of the late 18th century. Slave ports in Liverpool, Glasgow, and Bristol bolstered the economy, reflected in the magnificent Georgian buildings that still stand today. Not only did the traders gain wealth from their engagement in the slave trade, the nation became wealthy, too. By 1740 Liverpool was the biggest port of the slave trade in Britain, receiving slave ships arriving from Africa and hosting auctions of enslaved people for traders going to the Caribbean and North America. Africans enslaved in the Caribbean and North America were indeed separated from Britain by an ocean; thus, the products and the money existed in the foreground of British luxuriance, at a stark remove from the bloodied hands that made them. Public historian David Olusoga argues that the closer we look at the wealth of the British crown and aristocracy, the more these borders and separations break down. Though we may prefer to whitewash the landscape of Georgian, Regency, and Victorian Britain, visiting beautiful mansions and castles, and reveling in the delight of romantic period pieces, the reality is, enslaved “people, money, and ideas surged across the ocean,” making this shiny veneer possible.

Statue of former Prime Minister William Gladstone, inheritor of the wealth of his slave owning father, John Gladstone, accessed via, Victorian Web.

Slavery on British Soil

Let us tackle the myth head-on now: Slavery did, indeed, exist on British soil for over two and a half centuries. The stories of enslaved people in Britain have been easily painted over precisely because British law did not define the terms and conditions of enslavement. This lack of legislation makes it difficult even to establish how many enslaved people there were in Britain at any one time, as they do not appear as such on historical censuses, like they do in the colonial records. Particularly in the 17th and 18th centuries, the size of the Black British population is understood via estimates made in newspapers and court cases at the time. For example, in 1764, a London magazine suggested that the city alone had 20,000 Black residents, but did not connote their status as slave or free. During the Sommerset Trial in 1772, lawyers believed there were 15,000 in the city of London. By 1789, other records indicate the presence of 40,000 Black people across Britain. Although African and African descended people lived on British soil in the 17th and 18th centuries, it is evident that they made up a small portion of the population, just as we do now. White supremacists of the era sought Black expulsion from Britain, campaigning against the growing Black presence by claiming them to be a threat against the contamination of English blood, but failed to drum up enough alarm because the Black population was so small. Nonetheless, the Black presence in Britain was a palpable reminder of the brutalities British slavers were committing an ocean away.

Another reason the Black population of Britain in the Georgian era is difficult to ascertain is that such small numbers left legislators with no impulse to instigate segregation. This means that it is difficult to find any “Black communities” which we see emerge in the free states of America after the American Revolution, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and the boroughs of New York. Instead, Black people were scattered everywhere across London and other cities across the nation, rather than in any one community. Nonetheless, David Olusoga argues that both free and enslaved Black people were “numerous enough to have been a feature of city life, but still unusual enough to have remained an exotic novelty worthy of mention in the accounts of travellers and the reports of journalists.”

Africans arrived in Britain in numerous ways. Most arrived via the Transatlantic Slave Trade, when British slave ships docked in Liverpool, Bristol, and Glasgow to sell enslaved people on to slavers headed for the Caribbean and North America. Some merchants and British elite families would purchase enslaved people for retention in the UK to work as domestic servants, on the docks, or on other merchant and slave ships. Others arrived from the West Indies, brought by slave traders who claimed a few enslaved people for themselves and brought them back to work. Britain’s lack of definition surrounding the terms of enslavement made for the flexibility of the status that is unique to slavery on British soil. As David Olusoga highlights, many enslaved people who arrived in the UK “discovered that the borders between slavery and service were not nearly as well delineated in Britain as they were in the binary, slave societies of the West Indies and North America.” One benefit of this is that some were able to renegotiate their position, occupying a semi-manumitted state.

Perhaps the most famous instance of this was the life of world-renowned as the first “Black Dandy,” Julius Soubise. In 1764, British Royal Navy Captain Stair Douglass purchased Soubise as a 10-year-old from a Jamaican plantation, and gave him as a gift to Catherine Hyde Douglass, the Duchess of Queensberry in England. This purchase removed from the hard labor of Jamaican plantations, the “young Othello” was stripped of his name, christened Julius Soubise, and entered a different form of enslavement known as “pet people,” or “darling blacks,” or “privilege persons.” This version of enslavement functioned all over Europe, where European aristocracy held enslaved people as semi-manumitted persons, using them not for labor, but as status symbols who expressed their wealth.

In Soubise’s case, this manifested in being groomed by Douglass into a member of the aristocracy, training him in fencing and horse-riding, leading to his eventual mastery of both crafts and employment as an instructor. In addition to these aristocratic adornments, the duchess dressed Soubise in the latest fashions and fineries, for which he became famous. He became known to be seen “clad in a powdered wig, white silk breeches, very tight coat and vest, with an enormous white neck cloth, white silk stockings and diamond buckled red heeled shoes.” Soubise served as a companion and confidant to the duchess and elite men, as did countless others enslaved in this station. This dandification of Soubise may appear to be luxury at first glance, but for him and others like him, it further entrenched them in the objectification of enslavement. While under the patronage of Douglass, English society turned a blind eye to Soubise’s rumored womanizing and excessive drinking, celebrating his dress and skill.

However, Soubise gradually became increasingly independent, taking advantage of the liminal space he occupied as an enslaved man in Britain. He earned his own income as a horse-riding instructor, moved into an apartment for parties and female company, and continued to wear lavish clothing. Soon, white society saw his behaviour as decadence, demonstrative of a Black man untamed, too free, and, therefore, dangerous. He quickly became “known as one of the most conspicuous fops in town.” Historian Monica Miller argues that Soubise’s “crime of fashion” was simple: he “transformed white excess into black luxuriance,” undermining the rigid racial hierarchy of 18th-century England. Public disdain escalated, and Soubise was expelled to Calcutta, India, to reform his ways. Soubise’s rise and demise demonstrate the limitations of this flexible status of enslavement in Britain, which evidences the rigidity of British notions of the status Black people were supposed to occupy. By this time, the notion of the inherent inferiority of Blackness and Africanness was in place and shaped the lives of the many Black residents of Britain.

Black Brits of the 18th century, both enslaved and free, worked in a variety of service roles. Many worked as servants in the houses of the wealthy, or as liveried coachmen, pageboys, all roles which would have made them highly visible in British society, though they are often off to the side in the art of the time. Black men also found work as bandsmen in the army, or as sailors (both free and enslaved) on merchant ships and slave ships. Countless men worked as bargemen on banks, and men and women served at bars and taverns. Of course, as many occupied the working class, many ended up beggars on the streets, struggling to get by, leading some Black women into the thriving sex trade. Newspapers of London celebrated one Black woman known as Black Harriott, a courtesan who they believed had “attained a degree of politeness, scarce to be paralleled in an African female,” a racialized praise that illuminates not only Harriott’s life circumstances but also the British gaze upon their Black countrymen and women. Olusoga highlights theatre and music as arenas in which Black people found work, drawing crowds based on novelty to British audiences.

Further evidence of the presence of enslaved people in Britain throughout the 17th and 18th centuries is the presence of advertisements for the sale of enslaved people or rewards for the return of enslaved people who had run away. These newspapers reveal that sales of enslaved people could take place in the public square, but also at public houses. Additionally, through these sources we can see white art dealers advertising both artwork and enslaved people for sale, an unusual profile for a slave trader to the 21st-century mind.

A 1768 Runaway Slave Newspaper Advertisement, accessed via: Runaway Slaves in Britain

Historians have found hundreds of advertisements for the sale of enslaved people who would otherwise go to the West Indies in 18th century newspapers and periodicals. This is particularly interesting fiven the lack of law supporting and regulating the institution of slavery, and illuminates the reality that slavery was deeply embedded into custom, society, and culture, such that enslavers used these advertisements.

Ultimately, some Black people were able to integrate into white Britain through intermarriage and finding work and freedom, but countless others remained enslaved until their deaths. While enslavement in Britain presents as a deliverance from the brutalities of the West Indies and America, we must not assume it to be a benign institution. British enslavement featured violence, subjugation, and denial of rights. As David Olusoga notes, “unfreedom and slavery of black human beings was a feature of British life between the 1650s and the end of the 18th century,” long years that firmed up deeper ideas of race and Black inferiority.